|

E-Library

Supplementary Readings

About Canada—Canada's Cities

Although

Canada is still a vast expanse of forests, lakes, prairies and mountains,

Canadians have become largely a nation of city dwellers. With over

three-quarters of its population living in urban areas, and almost

one-third in large cities of more than a million, Canada is actually

one of the most urbanized countries in the world. The story of the

change from a rural to an urban society is thus an important part

of our history. Some of the common themes and variations of this

development can be illustrated by briefly examining the unique character

of a few important cities in eachregion in terms of their origins,

physical features, economy, ethnic composition, Although

Canada is still a vast expanse of forests, lakes, prairies and mountains,

Canadians have become largely a nation of city dwellers. With over

three-quarters of its population living in urban areas, and almost

one-third in large cities of more than a million, Canada is actually

one of the most urbanized countries in the world. The story of the

change from a rural to an urban society is thus an important part

of our history. Some of the common themes and variations of this

development can be illustrated by briefly examining the unique character

of a few important cities in eachregion in terms of their origins,

physical features, economy, ethnic composition,

|

|

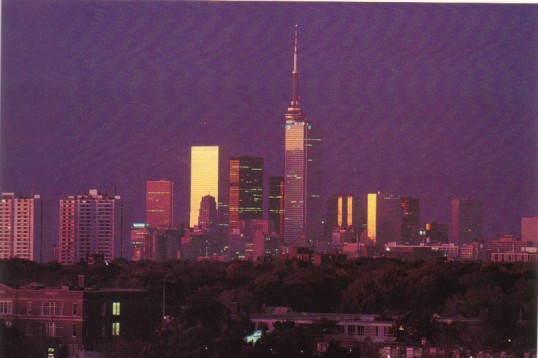

Toronto

|

|

|

Vancouver

|

cultural life, and patterns of growth.

Only a small sampling is possible here, but it is not entirely arbitrary:

Quebec is our oldest city and a symbol of French civilization in

North America; Halifax, our first British imperial city, is now

the major city of the Atlantic region; Montreal was Canada' bilingual

metropolis for a century and a half; its rival, Toronto, is now

the country's largest city, with anenormous concentration of financial

power and cultural influence; Sudbury exemplifies a city which has

survived the decline fo its resource-based economy through diversification;

Edmonton represents the new cities of the Prairies; and Vancouveris

the binding knot of Canada's growing economic and cultural ties

with Asia and the Pacific Rim.

Quebec: Canada's first city

When

the French explorer, Samuel de Champlain, founded Quebec City in

1608 atop the strategic cliffs where the St. Lawrence suddenly narrows

towards the west, his only intention was to defend the area from

rival fur traders. Quebec's role changed dramatically, however,

when the French government decided to make it much more than a trading

post and bastion against the British. Although the town remained

relatively small—its population was still only 2,000 in 1700—it

became the administrative, religious, military and cultural centre

of the royal colony of New France. When

the French explorer, Samuel de Champlain, founded Quebec City in

1608 atop the strategic cliffs where the St. Lawrence suddenly narrows

towards the west, his only intention was to defend the area from

rival fur traders. Quebec's role changed dramatically, however,

when the French government decided to make it much more than a trading

post and bastion against the British. Although the town remained

relatively small—its population was still only 2,000 in 1700—it

became the administrative, religious, military and cultural centre

of the royal colony of New France.

Quebec

City continued as an administrative centre after the British conquest

in 1759, but gradually declined in economic importance during the

19th century as new settlement further west made Montreal better

located to become the commercial centre of British North America.

Its ethnic compositon also changed dramatically during this period

as Anglophones came to account for nearly half the population by

1861. This has since been reversed, however; today the 600,000 strong

population fo the city and its suburbs is 96% Francophone. Quebec's

French cultural life (the province's as well as the city's) has

been greatly enriched by the Seminaire de Quebec. Founded in 1663,

it was one of the first educations institutions in North America.

Some two centuries later it became the nucleus of Laval University

(founded 1852). Quebec

City continued as an administrative centre after the British conquest

in 1759, but gradually declined in economic importance during the

19th century as new settlement further west made Montreal better

located to become the commercial centre of British North America.

Its ethnic compositon also changed dramatically during this period

as Anglophones came to account for nearly half the population by

1861. This has since been reversed, however; today the 600,000 strong

population fo the city and its suburbs is 96% Francophone. Quebec's

French cultural life (the province's as well as the city's) has

been greatly enriched by the Seminaire de Quebec. Founded in 1663,

it was one of the first educations institutions in North America.

Some two centuries later it became the nucleus of Laval University

(founded 1852).

In

appearance Quebec ramins the most European of North American cities.

Mus of its early character has been preserved in the historic centre,still

entered through a gate in the remaining portion of the town wall.

The commercial and residential buildings of the old Lower Town resemble

those of medieval French towns like Rouen in Normandy, while the

architecture of the rligious institutions of the Upper Town reflects

the Baroque style of seventeenth century Paris. Most of the fortifications

which dominate the site-the walls and the citadel-date from the

early 19th century when the Americans were considered a threat.

The modern city has grown out into the suburban fringes of Ste-Foy

and Charlesbourg, but the old city remains a unique relic of Canada's

earliest urban life. In

appearance Quebec ramins the most European of North American cities.

Mus of its early character has been preserved in the historic centre,still

entered through a gate in the remaining portion of the town wall.

The commercial and residential buildings of the old Lower Town resemble

those of medieval French towns like Rouen in Normandy, while the

architecture of the rligious institutions of the Upper Town reflects

the Baroque style of seventeenth century Paris. Most of the fortifications

which dominate the site-the walls and the citadel-date from the

early 19th century when the Americans were considered a threat.

The modern city has grown out into the suburban fringes of Ste-Foy

and Charlesbourg, but the old city remains a unique relic of Canada's

earliest urban life.

Halifax: Canada's gibraltar

For

most of its early history, Halifax's prosperity and growth depended

on its fluctuating military importance as fortress, naval base,

and garrison for troops. Founded in 1749, its original purpose was

simply to counter the military and economic threat of Louisbourg,

a French fortress on what is now Cape Breton Island. During the

Seven Years War, the American Revolution, and the Napoleonic Wars,

Halifax became a booming centre of British operations, but during

the intervening periods of peace, its economy stagnated. In the

middle decades of the 19th century, the "Golden Age of Sail", Halifax

competed successfully with its larger commercial rival, Saint John,

New Brunswick. But the industrializaiton that created rapid growth

in Central Canadian cities during the latter part of the century

largely by-passed the Atlantic region, partly because of distance

to markets, unfavourable freight rates to Central Canada, and increased

tariffs. For

most of its early history, Halifax's prosperity and growth depended

on its fluctuating military importance as fortress, naval base,

and garrison for troops. Founded in 1749, its original purpose was

simply to counter the military and economic threat of Louisbourg,

a French fortress on what is now Cape Breton Island. During the

Seven Years War, the American Revolution, and the Napoleonic Wars,

Halifax became a booming centre of British operations, but during

the intervening periods of peace, its economy stagnated. In the

middle decades of the 19th century, the "Golden Age of Sail", Halifax

competed successfully with its larger commercial rival, Saint John,

New Brunswick. But the industrializaiton that created rapid growth

in Central Canadian cities during the latter part of the century

largely by-passed the Atlantic region, partly because of distance

to markets, unfavourable freight rates to Central Canada, and increased

tariffs.

During

this century, Halifax has become the largest city of the Atlantic

region. It now has a metropolitan population of more than 300,000.

With its two large container terminals, it is also the region's

principal port. Its five universities and the Neptune Theatre are

some of the many examples of a vigorous educational tradition and

rich cultural life. People of British origin still make up about

80% of the population, a figure far higher than that of cities in

other regions of the country. During

this century, Halifax has become the largest city of the Atlantic

region. It now has a metropolitan population of more than 300,000.

With its two large container terminals, it is also the region's

principal port. Its five universities and the Neptune Theatre are

some of the many examples of a vigorous educational tradition and

rich cultural life. People of British origin still make up about

80% of the population, a figure far higher than that of cities in

other regions of the country.

Like

Quebec, Halifax still shows its historical roots. The original city

nestles on the side of an imposing hill, pressed tightly between

the two strategic sites that gave it birth-the citadel above and

the waterfront below. The present citadel dates from the 1850s and

, in spite of competition from the glass and steel structures below,

is still a commanding presence. The historic waterfront has been

partially restored and effectively recalls Halifax's great age of

sail. The original parade ground, once used for drilling troops,

is still the city's symbolic centre. Unlike the larger cities of

central and western Canada, Halifax still has fine wooden churches

and houses of all sizes near the downtown core. Like

Quebec, Halifax still shows its historical roots. The original city

nestles on the side of an imposing hill, pressed tightly between

the two strategic sites that gave it birth-the citadel above and

the waterfront below. The present citadel dates from the 1850s and

, in spite of competition from the glass and steel structures below,

is still a commanding presence. The historic waterfront has been

partially restored and effectively recalls Halifax's great age of

sail. The original parade ground, once used for drilling troops,

is still the city's symbolic centre. Unlike the larger cities of

central and western Canada, Halifax still has fine wooden churches

and houses of all sizes near the downtown core.

Montreal: the experience of a dual society

Montreal's

origins seem rather unlikely for a city destined to become the country's

metropolis for 150 years. Founded in 1642 by a French officer, Maisonneuve,

as a missionary post to the Indians, it was later granted to a religious

order, the Sulpicians, who shaped its character for generations.

However its location at the confluence of the St. Lawrence, Ottawa

and several other rivers also made it a natural centre of the fur

trade with the western native population. By the 1820s, general

trade and industry had transformed it into the major distributing

centre for Kingston, Toronto and other new towns on the western

frontier. It was propelled to national metropolitan status by a

combination of finance, transportation, and industry, all dominated

by Anglophones. The Bank of Montreal, founded in 1817, played a

pivotal role in making St. James Street (Rue St. Jacques in Old

Montreal) the financial centre of the country. Another important

player was the Canadian Pacific Railway, a Montreal-based syndicate

headed by George Stephen, who was also President of the Bank of

Montreal. Montreal's

origins seem rather unlikely for a city destined to become the country's

metropolis for 150 years. Founded in 1642 by a French officer, Maisonneuve,

as a missionary post to the Indians, it was later granted to a religious

order, the Sulpicians, who shaped its character for generations.

However its location at the confluence of the St. Lawrence, Ottawa

and several other rivers also made it a natural centre of the fur

trade with the western native population. By the 1820s, general

trade and industry had transformed it into the major distributing

centre for Kingston, Toronto and other new towns on the western

frontier. It was propelled to national metropolitan status by a

combination of finance, transportation, and industry, all dominated

by Anglophones. The Bank of Montreal, founded in 1817, played a

pivotal role in making St. James Street (Rue St. Jacques in Old

Montreal) the financial centre of the country. Another important

player was the Canadian Pacific Railway, a Montreal-based syndicate

headed by George Stephen, who was also President of the Bank of

Montreal.

In

more recent years, Montreal gained international stature by hosting

Expo 67 and the Summer Olympics of 1976. However, economic decline

has since eroded the city's once dominant positon within Canada.

The rise of Quebec sparatism, followed by new language laws, has

also led a number of large firms to move their headquarters to Toronto,

and prompted a number of Anglophones to leave the province. In

more recent years, Montreal gained international stature by hosting

Expo 67 and the Summer Olympics of 1976. However, economic decline

has since eroded the city's once dominant positon within Canada.

The rise of Quebec sparatism, followed by new language laws, has

also led a number of large firms to move their headquarters to Toronto,

and prompted a number of Anglophones to leave the province.

Competing

interests between Anglophone and Francophone have been a feature

of Montreal socity since the conquest. British immigrants created

an Anglophone majority between 1831 and 1867. Industrialization

reversed the balance by attracting a large inflow from rural Quebec,

but an English-speaking business elite continued to dominate the

city's economic life until the mid-70s. During recent decades the

Francophone population has risen to about 66% of the total (compared

to 82% for the province) while the language and sign laws have again

made French the language of the workplace. Competing

interests between Anglophone and Francophone have been a feature

of Montreal socity since the conquest. British immigrants created

an Anglophone majority between 1831 and 1867. Industrialization

reversed the balance by attracting a large inflow from rural Quebec,

but an English-speaking business elite continued to dominate the

city's economic life until the mid-70s. During recent decades the

Francophone population has risen to about 66% of the total (compared

to 82% for the province) while the language and sign laws have again

made French the language of the workplace.

Based

on a plan laid out in the 1670s by Dollier de Casson, Head of the

Sulpician Order, and possibl Canada's first town plnner, Montreal's

downtown core for much of its history was a rectangular grid beside

the St. Lawrence. During the 19th centur the city expanded up and

around Mount Royal, its most striking topographic feature. Much

of the downtown residential area, once the quartiers populaires

of rural immigrants, is still dominated by turn-of-the-century houses

with their characteristic outdoor wrought-iron stairways. The shift

to a new downtown core began in the late 1950s with the construction

of Place Ville-Marie on Dorchester (now Rene Levesque) Boulevard.

A Parisian-style subway sstem, with cars running on quiet rubber

tires, was completed just before Expo 67. Together with a vast underground

system of shops and pedestrian walk-ways, this has drained some

of the life out of streets that were once the most vibrant in Canada.

But despite all the changes and challenges, Montreal is still the

most culturally complex and, to many, still the most interesting

city in Canada. Based

on a plan laid out in the 1670s by Dollier de Casson, Head of the

Sulpician Order, and possibl Canada's first town plnner, Montreal's

downtown core for much of its history was a rectangular grid beside

the St. Lawrence. During the 19th centur the city expanded up and

around Mount Royal, its most striking topographic feature. Much

of the downtown residential area, once the quartiers populaires

of rural immigrants, is still dominated by turn-of-the-century houses

with their characteristic outdoor wrought-iron stairways. The shift

to a new downtown core began in the late 1950s with the construction

of Place Ville-Marie on Dorchester (now Rene Levesque) Boulevard.

A Parisian-style subway sstem, with cars running on quiet rubber

tires, was completed just before Expo 67. Together with a vast underground

system of shops and pedestrian walk-ways, this has drained some

of the life out of streets that were once the most vibrant in Canada.

But despite all the changes and challenges, Montreal is still the

most culturally complex and, to many, still the most interesting

city in Canada.

Toronto: from loyalist community to multicultural metropolis

Toronto

long remained the conserative British community that John Graves

Simcoe, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, founded in 1792. Protestant,

puritanical, and loyal to Britain, the ruling group he helped to

establish shaped the town for generations. By the time it officially

became a city in 1834, it had already replaced Kingston as the commercial

centre of Upper Canada. It became even more dominant during the

1850s when its businessmen built a network of railroads to other

parts of the province. Like Montreal, Toronto carried a good deal

of weight in federal politics and this greatly facilitated its industrialization

during the second half of the 19th century. For example, a national

baning act centralized financial control in these two cities while

a national tariff policy further strengthened the already well-established

industry of Central Canada. Toronto

long remained the conserative British community that John Graves

Simcoe, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, founded in 1792. Protestant,

puritanical, and loyal to Britain, the ruling group he helped to

establish shaped the town for generations. By the time it officially

became a city in 1834, it had already replaced Kingston as the commercial

centre of Upper Canada. It became even more dominant during the

1850s when its businessmen built a network of railroads to other

parts of the province. Like Montreal, Toronto carried a good deal

of weight in federal politics and this greatly facilitated its industrialization

during the second half of the 19th century. For example, a national

baning act centralized financial control in these two cities while

a national tariff policy further strengthened the already well-established

industry of Central Canada.

In

the years after World War II, Toronto overtook Montreal as the country's

largest city, and Bay Street replaced St. James Street as its chief

financial centre. As in all North American cities, industry gradually

moved from downtown to the suburbs, or fled the country entirely.

This new suburban industry is highly specialized, with the largest

component now in the automotive sector. With plants in Oakville,

Oshawa, and Brampton, the Toronto area is, in North America, second

only to Detroit in this field. In

the years after World War II, Toronto overtook Montreal as the country's

largest city, and Bay Street replaced St. James Street as its chief

financial centre. As in all North American cities, industry gradually

moved from downtown to the suburbs, or fled the country entirely.

This new suburban industry is highly specialized, with the largest

component now in the automotive sector. With plants in Oakville,

Oshawa, and Brampton, the Toronto area is, in North America, second

only to Detroit in this field.

Toronto's

graduation from a provincial to a national city was accompanied

by dramatic changes in its ehnic make-up. During the 19th centur,

Torontonians were overwhelmingly of British origin, although Irish

Catholics, soon comprised one quarter of the population. Non-British

immigration began early in this century but the major changes came

after WWII, and from a great variety of sources. By the time of

the 1991 Census, successive waves of immigration from Eastern and

Southern Europe (chiefly Italian, Greek, and Portuguese), the Caribbean,

and Asia (mainly Chinese and Vietnamese) had reduced the proportion

of those of British/Irish origin to about 40%. Today Toronto is

the only major Canadian city where the majority is of neither British

nor French descent. Toronto's

graduation from a provincial to a national city was accompanied

by dramatic changes in its ehnic make-up. During the 19th centur,

Torontonians were overwhelmingly of British origin, although Irish

Catholics, soon comprised one quarter of the population. Non-British

immigration began early in this century but the major changes came

after WWII, and from a great variety of sources. By the time of

the 1991 Census, successive waves of immigration from Eastern and

Southern Europe (chiefly Italian, Greek, and Portuguese), the Caribbean,

and Asia (mainly Chinese and Vietnamese) had reduced the proportion

of those of British/Irish origin to about 40%. Today Toronto is

the only major Canadian city where the majority is of neither British

nor French descent.

Laid

out in a grid pattern along Lake Ontario, Toronto's flatness is

unrelieved by any strong natural feature. Until recently, it was

more compact than most cities, making public transportation a more

workable alternative to the automobile than elsewhere. Downtown

neighourhoods have thus remained viable, indeed desirable, places

to live. Major cultural and educational facilities such as the Royal

Ontario Museum, the Ontario Art Gallery, the Univeristy of Toronto,

Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, the CBC, and a number of national

publishing firms remain concentrated in the downtown area. Large

bank towers dominate much of the skyline, but the best-known architectural

shapes are those of the CN Tower and the Skydome. Laid

out in a grid pattern along Lake Ontario, Toronto's flatness is

unrelieved by any strong natural feature. Until recently, it was

more compact than most cities, making public transportation a more

workable alternative to the automobile than elsewhere. Downtown

neighourhoods have thus remained viable, indeed desirable, places

to live. Major cultural and educational facilities such as the Royal

Ontario Museum, the Ontario Art Gallery, the Univeristy of Toronto,

Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, the CBC, and a number of national

publishing firms remain concentrated in the downtown area. Large

bank towers dominate much of the skyline, but the best-known architectural

shapes are those of the CN Tower and the Skydome.

Previous Page Next

Page

|