5.3 Different approaches to syntax

Knowledge of sentence structure is the object of study of all schools of grammar. One school of grammar is comparatively more successful in dealing with certain aspects of syntax than another. Among all grammars, four appear to be well recognized, namely, traditional grammar, structural grammar, transformational generative grammar and systemic-functional grammar.

Traditional grammar was initially based on European languages, particularly on Latin and Greek. It is the most widespread and elaborate grammar and is widely used in language teaching, thus termed pedagogic grammar. In analyzing sentences, the method adopted is called parsing. This generally involves five aspects: (1) identifying elements of the sentence, labeling the parts as subject, predicate, object, attribute, adverbial, etc.; (2) identifying part of speech of each word; (3) pointing out the inflection of the words; (4) describing the relationship between the words; (5) generalizing the order of words. Fundamentally, this approach to the analysis of sentence structure is notional in nature. It classifies words and parts of sentences mainly according to meaning.

While traditional grammar is well established, its weaknesses are pinpointed by modern linguists. Firstly, it is prescriptive in nature, attempting to lay down rules for speakers of a language. Secondly, its grammatical categories are merely based on European languages and are found inadequate in describing other languages. Thirdly, it lacks a theoretical framework and thus fails to account for the nature of language.

Structural grammar arose out of an attempt to deviate from traditional grammar. In the early years of the twentieth century, American anthropologists and linguists began to describe American Indian languages, as many of these tribal languages were dying. They tried to innovate ways of analysis, because they found some traditional grammatical categories based on European languages unfeasible in describing those native languages of America. Among their innovations, two concepts are influential in linguistic studies.

One is the idea of form class, which is a wider concept than part of speech. Linguistic units which can appear in the same slot are said to be in the same form class. For example, a(n), the, my, that, every, etc, can be placed before nouns in English sentences. These words fall into one form class. To put it technically, these linguistic units are observed to have the same distribution. This formal approach to syntactic categories is more practicable in observing and analyzing unknown languages.

The other important concept of structural grammar is the concept of immediate constituent. Unlike traditional grammar, which adopts a synthetic (bottom-up) approach to syntax, structural grammar is characterized by a top-down process of analysis. A sentence is seen as a constituent structure. All the components of the sentence are its constituents. A sentence can be cut into sections. Each section is its immediate constituent. Then each section can be further cut into constituents. This on-going cutting is termed immediate constituent analysis.

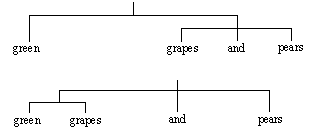

This way of syntactic analysis adds a new dimension to the analysis of sentence structure. In this way, sentence structure is analyzed not only horizontally but also vertically. In other words, immediate constituent analysis can account for the linearity and the hierarchy of sentence structure, and, therefore, structural ambiguity. Take the sentence I like green grapes and pears, for example. It can be cut in two ways. In the phrase green grapes and pears, there can be two different sets of immediate constituents.

The analysis shows clearly that the linear structure is the same but

the hierarchical structures are different. That is why the phrase green

grapes and pears can be interpreted in two ways.

While structural grammar represents a departure from traditional grammar

and an attempt to describe all languages objectively, it has its limitations.

Practically it is not comparable to traditional grammar in achievement

in that no pedagogic grammar of a language has been written following

this approach. Theoretically, no breakthrough is made in understanding

the nature of language. Methodologically, immediate constituent analysis,

with all its merits, has met challenge from new linguistic data which

it fails to account for. Since the 1950s, two complementary schools of

grammar have been developing as theoretical explorations into language.

Their fundamental concepts and methods will be introduced in the rest

of this chapter.