|

● Religious

Liberty

● Protestants

in the United States

● CathoLics

● Three

Faiths

● Religious

Diversity

● American

Character of Religion

Text

|

|

Worship

by Early Protestant Settlers

|

From

Chapter 1, we came to know that American mainstream culture was

developed from what is known as "WASP"

culture and that people who settled in the 13 North American

colonies that would become the United States were mostly Protestant

believers. From

Chapter 1, we came to know that American mainstream culture was

developed from what is known as "WASP"

culture and that people who settled in the 13 North American

colonies that would become the United States were mostly Protestant

believers.

Religious Liberty

|

|

A

Puritan Girl

|

By

the middle of the 18th century, many different kinds of Protestants

lived in America. Lutherans

had come to America from Germany. The

Dutch Reformed Church flourished in New York and New Jersey.

Presbyterians

came from Scotland and Huguenots

from France.

Congregationalists, as the Puritans

came to be called, still dominated in Massachusetts and the neighboring

colonies, an area which came to be known as New England. By

the middle of the 18th century, many different kinds of Protestants

lived in America. Lutherans

had come to America from Germany. The

Dutch Reformed Church flourished in New York and New Jersey.

Presbyterians

came from Scotland and Huguenots

from France.

Congregationalists, as the Puritans

came to be called, still dominated in Massachusetts and the neighboring

colonies, an area which came to be known as New England.

Although

the Church of England

was an established

church in several colonies, Protestants lived side by side in relative

harmony, and they influenced each other. The

Great Awakening of the 1740s, a "revival" movement

that sought to breathe new feeling and strength into religion, cut

across the lines of Protestant religious groups, or denominations. Although

the Church of England

was an established

church in several colonies, Protestants lived side by side in relative

harmony, and they influenced each other. The

Great Awakening of the 1740s, a "revival" movement

that sought to breathe new feeling and strength into religion, cut

across the lines of Protestant religious groups, or denominations.

At

the same time the works of John

Locke were becoming known in America. John

Locke reasoned that the right to govern comes from an agreement

or "social contract" voluntarily entered into by free

people. The Puritan experience in forming congregations

made this idea seem natural to many Americans. Taking it out of

the realm

of social theory, they made it a reality and formed a nation. At

the same time the works of John

Locke were becoming known in America. John

Locke reasoned that the right to govern comes from an agreement

or "social contract" voluntarily entered into by free

people. The Puritan experience in forming congregations

made this idea seem natural to many Americans. Taking it out of

the realm

of social theory, they made it a reality and formed a nation.

It

was politics and not religion that most occupied Americans' minds

during the War of Independence and for years afterward. A few Americans

were so influenced by the new science and new ideas of the

Enlightenment

in Europe that they became deists,

believing

that reason teaches that God exists but leaves man free to settle

his own affairs. It

was politics and not religion that most occupied Americans' minds

during the War of Independence and for years afterward. A few Americans

were so influenced by the new science and new ideas of the

Enlightenment

in Europe that they became deists,

believing

that reason teaches that God exists but leaves man free to settle

his own affairs.

Many

traditional Protestants and deists could agree, however, that, as

The Declaration of Independence states, "all men are

created equal, that they are endowed

by their creator with certain unalienable

rights," and that "the

laws of Nature and Nature's God" entitled them to form a new

nation. Among

the rights that the new nation guaranteed, as a political necessity

in a religiously diverse society, was freedom of religion. Many

traditional Protestants and deists could agree, however, that, as

The Declaration of Independence states, "all men are

created equal, that they are endowed

by their creator with certain unalienable

rights," and that "the

laws of Nature and Nature's God" entitled them to form a new

nation. Among

the rights that the new nation guaranteed, as a political necessity

in a religiously diverse society, was freedom of religion.

The

First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

forbade the new federal government to give special favors to any

religion or to hinder the free practice, or exercise, of religion.

The Unites States would have no state-supported religion. In

this way, those men who formulated

the

principal

tenets

of

the newly established political system hoped to insure that diversity

of religious belief would never become the source of social or political

injustice or disaffection. But Protestant churches kept

a privileged position in a few of the states. Not

until 1833 did Massachusetts cut the last ties between church and

state. The

First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

forbade the new federal government to give special favors to any

religion or to hinder the free practice, or exercise, of religion.

The Unites States would have no state-supported religion. In

this way, those men who formulated

the

principal

tenets

of

the newly established political system hoped to insure that diversity

of religious belief would never become the source of social or political

injustice or disaffection. But Protestant churches kept

a privileged position in a few of the states. Not

until 1833 did Massachusetts cut the last ties between church and

state.

The

First Amendment insured that American government would not meddle

in religious affairs or require any religious beliefs of its citizens.

But did it mean that the American government would have nothing

at all to do with religion? Or did it mean that government would

be religiously neutral, treating all religions alike? The

First Amendment insured that American government would not meddle

in religious affairs or require any religious beliefs of its citizens.

But did it mean that the American government would have nothing

at all to do with religion? Or did it mean that government would

be religiously neutral, treating all religions alike?

|

|

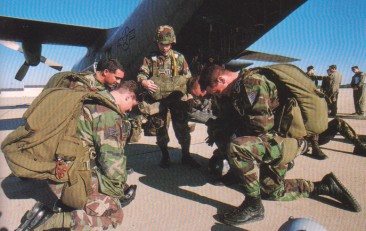

A

Priest in the Army

|

In

some ways, the government supports all religions. Religious groups

do not pay taxes in the United States. The armed forces pay chaplains

of all faiths. Presidents and other political leaders often

call on God to bless the American nation and people. Those people

whose religion forbids them to fight can perform other services

instead of becoming soldiers. In

some ways, the government supports all religions. Religious groups

do not pay taxes in the United States. The armed forces pay chaplains

of all faiths. Presidents and other political leaders often

call on God to bless the American nation and people. Those people

whose religion forbids them to fight can perform other services

instead of becoming soldiers.

But

government does not pay ministers'

salaries or require any belief—not even a belief in God—as a condition

of holding public office. Oaths are administered, but those who,

like Quakers,

object to them, can make a solemn affirmation, or declaration, instead. But

government does not pay ministers'

salaries or require any belief—not even a belief in God—as a condition

of holding public office. Oaths are administered, but those who,

like Quakers,

object to them, can make a solemn affirmation, or declaration, instead.

|

|

The

Supreme Court Justices

|

The

truth is that for some purposes government ignores religion and

for other purposes it treats all religions alike—at least as far

as is practical. When disputes about the relationship between government

and religion arise, American courts must settle them. The

truth is that for some purposes government ignores religion and

for other purposes it treats all religions alike—at least as far

as is practical. When disputes about the relationship between government

and religion arise, American courts must settle them.

American

courts have become more sensitive in recent years to the rights

of people who do not believe in any God or religion. But in many

ways what Supreme

Court Justice

William O. Douglas wrote in 1952 is still true. "We

are a religious people," he declared, "whose institutions

presuppose a Supreme Being." American

courts have become more sensitive in recent years to the rights

of people who do not believe in any God or religion. But in many

ways what Supreme

Court Justice

William O. Douglas wrote in 1952 is still true. "We

are a religious people," he declared, "whose institutions

presuppose a Supreme Being."

In

the early years of the American nation, Americans were confident

that God supported their experiment in republican government. They

had just defeated Great Britain—probably the most powerful nation

in the world at that time. Protestant religion and republican forms

of government, they felt, went hand

in hand. In

the early years of the American nation, Americans were confident

that God supported their experiment in republican government. They

had just defeated Great Britain—probably the most powerful nation

in the world at that time. Protestant religion and republican forms

of government, they felt, went hand

in hand.

Previous Page Next

Page

|