● Going

to School in America Today

● Education—A Local Matter

● What

an American Student Learns

● Education

in a New Nation

● Learning

to Be World Citizens

● Higher Education

● Selecting

a College or University

● Trends in Degree Programs

● Education for All

Education for All

In

1944 Congress passed the Servicemen's Readjustment Act, soon popularly

called the "GI

Bill of Rights." ("GI" at the time, was a

nickname for the American soldier. The nickname came from an abbreviation

for "Government Issue"—the uniforms and other articles

"issued" to a soldier.) The Act promised financial aid,

including aid for higher education, to members of the armed forces

after the end of World War II. In

1944 Congress passed the Servicemen's Readjustment Act, soon popularly

called the "GI

Bill of Rights." ("GI" at the time, was a

nickname for the American soldier. The nickname came from an abbreviation

for "Government Issue"—the uniforms and other articles

"issued" to a soldier.) The Act promised financial aid,

including aid for higher education, to members of the armed forces

after the end of World War II.

The

war ended in the following year. The prediction had been that 600

000 war veterans would apply for aid for education. By 1955, more

than two million veterans of World War II and of the Korean War

had used the GI Bill of Rights to go to college. Many of these veterans

were from poor families. 30% were married when they applied for

college aid; 10% had children. More than a few had to work part

time while they took courses. It was difficult, but these veterans

believed that a college degree (which they could not afford on their

own) would improve their chances for a good job in the postwar economy.

Some went to liberal arts colleges; others to technical and professional

institutions. Their outstanding success in all these schools forced

everyone connected with higher education to rethink its purpose

and goals. Within just a few years, American veterans

had changed the image of who should go to college. In postwar America,

other groups sought their place on America's campuses, too. The

enrollment of women in higher education began to increase. Racial

segregation in elementary and secondary education ended, and thus

blacks achieved an equal opportunity to get into any college of

their choice. The

war ended in the following year. The prediction had been that 600

000 war veterans would apply for aid for education. By 1955, more

than two million veterans of World War II and of the Korean War

had used the GI Bill of Rights to go to college. Many of these veterans

were from poor families. 30% were married when they applied for

college aid; 10% had children. More than a few had to work part

time while they took courses. It was difficult, but these veterans

believed that a college degree (which they could not afford on their

own) would improve their chances for a good job in the postwar economy.

Some went to liberal arts colleges; others to technical and professional

institutions. Their outstanding success in all these schools forced

everyone connected with higher education to rethink its purpose

and goals. Within just a few years, American veterans

had changed the image of who should go to college. In postwar America,

other groups sought their place on America's campuses, too. The

enrollment of women in higher education began to increase. Racial

segregation in elementary and secondary education ended, and thus

blacks achieved an equal opportunity to get into any college of

their choice.

By

the end of 1960s, some colleges introduced special plans and programs

to equalize educational opportunities—at every level, for all groups.

Some of these plans were called "Affirmative

Action Programs." Their goal was to make up for past

inequality by giving special reference to members of minorities

seeking jobs or admission to college. (In the United States, the

term "minority" has two meanings, often related: (a) A

minority is any ethnic or racial group that makes up a small percentage

of the total population; (b) The term also suggests a group that

is not the dominant political power.) Some colleges, for example,

sponsored programs to help minority students prepare for college

while still in high school. By

the end of 1960s, some colleges introduced special plans and programs

to equalize educational opportunities—at every level, for all groups.

Some of these plans were called "Affirmative

Action Programs." Their goal was to make up for past

inequality by giving special reference to members of minorities

seeking jobs or admission to college. (In the United States, the

term "minority" has two meanings, often related: (a) A

minority is any ethnic or racial group that makes up a small percentage

of the total population; (b) The term also suggests a group that

is not the dominant political power.) Some colleges, for example,

sponsored programs to help minority students prepare for college

while still in high school.

By

the 1970s, the United States government stood firmly behind such

goals. It required colleges and universities receiving public funds

to practice some form of affirmative action. But when colleges began

to set quotas (fixed numbers) of minority students to be

admitted, many Americans (including minority citizens) protested.

They felt that this was another form of discrimination. By

the 1970s, the United States government stood firmly behind such

goals. It required colleges and universities receiving public funds

to practice some form of affirmative action. But when colleges began

to set quotas (fixed numbers) of minority students to be

admitted, many Americans (including minority citizens) protested.

They felt that this was another form of discrimination.

|

|

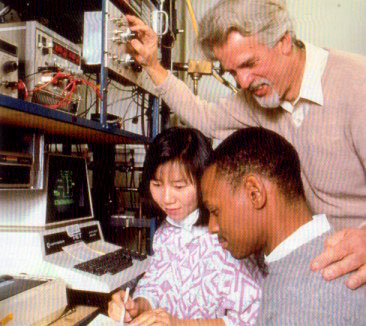

Minority Students

|

As

with most (but not all) problems in American public life, the conflict

was resolved by change and compromise. Colleges continued to serve

the goal of affirmative action—but in less controversial

ways. One large university, for example, announced a new policy:

It would seek to admit students who would add diverse talents to

the student body. It thus dealt with all applicants—minorities

included—on a basis that was not restricted to high school performance

and entrance tests, but which took into account the talents, voluntary

activities and "life experience" of the student. What

success did these efforts have? American college students are an

increasingly diverse group. In 1987, 54% were women. Women received

51% of the bachelor's and master's degrees awarded that year, and

35% of the doctorates and professional degrees. But not all groups

are doing so well. As

with most (but not all) problems in American public life, the conflict

was resolved by change and compromise. Colleges continued to serve

the goal of affirmative action—but in less controversial

ways. One large university, for example, announced a new policy:

It would seek to admit students who would add diverse talents to

the student body. It thus dealt with all applicants—minorities

included—on a basis that was not restricted to high school performance

and entrance tests, but which took into account the talents, voluntary

activities and "life experience" of the student. What

success did these efforts have? American college students are an

increasingly diverse group. In 1987, 54% were women. Women received

51% of the bachelor's and master's degrees awarded that year, and

35% of the doctorates and professional degrees. But not all groups

are doing so well.

|

|

Smith College—A

Private Women's College

|

Although

59% of the students who graduated from high school in 1988 enrolled

in college that same year, only 45% of the African-American high

school graduates went on to college. Educators and others are working

to increase that percentage. Although

59% of the students who graduated from high school in 1988 enrolled

in college that same year, only 45% of the African-American high

school graduates went on to college. Educators and others are working

to increase that percentage.

U.S.

colleges and universities are also enrolling a higher percentage

of non-traditional students—students who have worked for several

years before starting college or students who go to school part-time

while holding down a job. In 1987, 41% of college students were

25 years of age or older and 43% were part-time students. U.S.

colleges and universities are also enrolling a higher percentage

of non-traditional students—students who have worked for several

years before starting college or students who go to school part-time

while holding down a job. In 1987, 41% of college students were

25 years of age or older and 43% were part-time students.

Previous Page Next

Page

|