|

● Racial Problems

● Poverty

● Drug Abuse

● Crime

● The Abuse of Power

by Government and Corporations

Text

Racial Problems

|

|

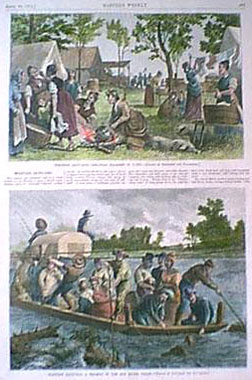

Early Immigrants Arrviving in the New World

|

Unlike

most other peoples, Americans are primarily a nation of immigrants.

The citizens or their ancestors immigrated from many parts of the

globe—some as refugees from religious and political persecution,

some as adventurers from the

Old World seeking a better life, some as captives

brought

to America against their own will to be sold into slavery.

Though people all share a common American culture, the

nation contains many racial and ethnic subcultures with their own

distinctive characteristics. These differences might

seem trivial

or irrelevant

to outside observers, but they have contributed

to racial conflicts that have been a persistent social problem to

American society. Unlike

most other peoples, Americans are primarily a nation of immigrants.

The citizens or their ancestors immigrated from many parts of the

globe—some as refugees from religious and political persecution,

some as adventurers from the

Old World seeking a better life, some as captives

brought

to America against their own will to be sold into slavery.

Though people all share a common American culture, the

nation contains many racial and ethnic subcultures with their own

distinctive characteristics. These differences might

seem trivial

or irrelevant

to outside observers, but they have contributed

to racial conflicts that have been a persistent social problem to

American society.

|

|

The Slave Trade Routes

|

|

| The white Anglo-Saxon

Puritans |

The

United States was founded on the principle of human equality, but

in practice the nation has fallen far short of that ideal.

American society is a stratified

one, in which power, wealth, and prestige

are unequally distributed

among the population. This inequality is not simply a matter of

distinctions between social classes; it tends to follow racial and

ethnic lines as well, with the result that class

divisions often parallel racial divisions. The first

settlers from "Anglo-Saxon" northern Europe quickly took

control of economic

assets and political power in the United States, and

they have maintained this control, to a greater or lesser degree,

ever since. Successive

waves of immigrants from other parts of Europe and elsewhere in

the world have had to struggle long and hard to become assimilated

into the mainstream of American life. Some have succeeded and have

shared in the "American

dream"; others notably those whose ethnic or racial

characteristics differ most markedly from those of the dominant

groups have been excluded by formal

and informal barriers from full participation in American

life . The result of this discrimination has been a severe and continuing

racial tension in the United States that has periodically erupted

into outright

violence. Particularly since the civil rights demonstrations, ghetto

riots,

and other unrest in the 1960s, race

and ethnic relations have been a major preoccupation

of

social scientists, politicians and the general public. The

United States was founded on the principle of human equality, but

in practice the nation has fallen far short of that ideal.

American society is a stratified

one, in which power, wealth, and prestige

are unequally distributed

among the population. This inequality is not simply a matter of

distinctions between social classes; it tends to follow racial and

ethnic lines as well, with the result that class

divisions often parallel racial divisions. The first

settlers from "Anglo-Saxon" northern Europe quickly took

control of economic

assets and political power in the United States, and

they have maintained this control, to a greater or lesser degree,

ever since. Successive

waves of immigrants from other parts of Europe and elsewhere in

the world have had to struggle long and hard to become assimilated

into the mainstream of American life. Some have succeeded and have

shared in the "American

dream"; others notably those whose ethnic or racial

characteristics differ most markedly from those of the dominant

groups have been excluded by formal

and informal barriers from full participation in American

life . The result of this discrimination has been a severe and continuing

racial tension in the United States that has periodically erupted

into outright

violence. Particularly since the civil rights demonstrations, ghetto

riots,

and other unrest in the 1960s, race

and ethnic relations have been a major preoccupation

of

social scientists, politicians and the general public.

In

the United States, any group other than the dominant white

Anglo-Saxon Protestant majority is a minority group in American

society. These racial and ethnic minorities mainly refer to the

blacks, Native Americans or American Indians, the Hispanics, and

Asian Americans. The social and economic conditions of Native Americans

are probably worse than those of any other minority groups. All

these racial groups including Asian

Americans are still suffering from racial discrimination

and injustice. But here we look more closely at one of them whose

problems have attracted the most public attention: the blacks or

Afro-Americans. In

the United States, any group other than the dominant white

Anglo-Saxon Protestant majority is a minority group in American

society. These racial and ethnic minorities mainly refer to the

blacks, Native Americans or American Indians, the Hispanics, and

Asian Americans. The social and economic conditions of Native Americans

are probably worse than those of any other minority groups. All

these racial groups including Asian

Americans are still suffering from racial discrimination

and injustice. But here we look more closely at one of them whose

problems have attracted the most public attention: the blacks or

Afro-Americans.

The

largest of the racial and ethnic minorities in the United States

is the blacks, who number over 25.2 million, or 11.7% of the population.

Their history in the United States has been one of sustained

oppression, discrimination, and denial of basic civil rights and

liberties. The

largest of the racial and ethnic minorities in the United States

is the blacks, who number over 25.2 million, or 11.7% of the population.

Their history in the United States has been one of sustained

oppression, discrimination, and denial of basic civil rights and

liberties.

The

first blacks were brought to North America in 1619. Within a few

decades the demand for their cheap labor led to a massive

slave trade that ultimately transported some 400 000 Africans to

this continent. Captured by neighboring tribes in their native villages

and then sold to white traders, the slaves were shipped in wretchedly

crowded conditions to the

Caribbean and then to the United States, where they were

sold like cattle

at auctions.

The

myth of their racial inferiority—their

irresponsibility, promiscuity,

laziness

and lower intelligence as assiduously

propagated

as

a justification

for

their continued subjugation. The

whip

or

the lynch

mob

served

to assert

social

control over slaves who challenged the established order. The

first blacks were brought to North America in 1619. Within a few

decades the demand for their cheap labor led to a massive

slave trade that ultimately transported some 400 000 Africans to

this continent. Captured by neighboring tribes in their native villages

and then sold to white traders, the slaves were shipped in wretchedly

crowded conditions to the

Caribbean and then to the United States, where they were

sold like cattle

at auctions.

The

myth of their racial inferiority—their

irresponsibility, promiscuity,

laziness

and lower intelligence as assiduously

propagated

as

a justification

for

their continued subjugation. The

whip

or

the lynch

mob

served

to assert

social

control over slaves who challenged the established order.

The

Northern states had all outlawed

slavery by 1830, but the Southern states, in which slaves had become

the backbone

of the economy, maintained the institution until

it was finally ended by the

Civil War, Lincoln's

emancipation

of

slaves in 1863, and the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1865.

But even after the abolition of slavery, wholesale

discrimination was practiced against black Americans. Many

states passed segregation

laws

to keep the races apart in schools, housing, restaurants, and other

public facilities, and institutionalized discrimination kept blacks

in the lowest-paid jobs. A variety of methods, such as

rigged

"literacy" tests, were used to keep blacks off

the voters' rolls and thus prevent them from exercising their political

rights. Segregation

laws continued to be enforced in Southern states until the 1950s;

in the North informal methods were used—often just as effectively. The

Northern states had all outlawed

slavery by 1830, but the Southern states, in which slaves had become

the backbone

of the economy, maintained the institution until

it was finally ended by the

Civil War, Lincoln's

emancipation

of

slaves in 1863, and the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1865.

But even after the abolition of slavery, wholesale

discrimination was practiced against black Americans. Many

states passed segregation

laws

to keep the races apart in schools, housing, restaurants, and other

public facilities, and institutionalized discrimination kept blacks

in the lowest-paid jobs. A variety of methods, such as

rigged

"literacy" tests, were used to keep blacks off

the voters' rolls and thus prevent them from exercising their political

rights. Segregation

laws continued to be enforced in Southern states until the 1950s;

in the North informal methods were used—often just as effectively.

|

| Black pride |

The

1960s saw the great civil rights movement whose goals were

to end segregation laws completely and fight for the equal rights

for the colored people. Many American blacks began to have a new

mood. They had feelings of pride; they declared that "black

is beautiful"; and the black community showed signs of unprecedented

self-confidence. Equally important, many black leaders began to

disclaim

full integration

into the American mainstream as the goal of the black minority.

Instead, they argued, blacks ought to coexist with other groups

in a plural society containing different and distinctive communities

living in mutual respect. The

1960s saw the great civil rights movement whose goals were

to end segregation laws completely and fight for the equal rights

for the colored people. Many American blacks began to have a new

mood. They had feelings of pride; they declared that "black

is beautiful"; and the black community showed signs of unprecedented

self-confidence. Equally important, many black leaders began to

disclaim

full integration

into the American mainstream as the goal of the black minority.

Instead, they argued, blacks ought to coexist with other groups

in a plural society containing different and distinctive communities

living in mutual respect.

The

current status of black Americans presents a mixed picture. The

elimination

of legal barriers to their advancement

has been a major gain, but institutionalized discrimination is still

rife.

Housing in particular, remains highly segregated: the great majority

of blacks continue to live in neighborhoods that are overwhelmingly

black, and most whites live in neighborhoods that are overwhelmingly

white. Busing

and other programs aimed at integrating the schools have had some

impact in inner-city areas but have made virtually no difference

to the segregation that exists between predominantly black urban

centers and the predominantly white suburbs and small towns that

surround them. Blacks have achieved considerable educational

gains; black enrollment in colleges rose spectacularly between The

current status of black Americans presents a mixed picture. The

elimination

of legal barriers to their advancement

has been a major gain, but institutionalized discrimination is still

rife.

Housing in particular, remains highly segregated: the great majority

of blacks continue to live in neighborhoods that are overwhelmingly

black, and most whites live in neighborhoods that are overwhelmingly

white. Busing

and other programs aimed at integrating the schools have had some

impact in inner-city areas but have made virtually no difference

to the segregation that exists between predominantly black urban

centers and the predominantly white suburbs and small towns that

surround them. Blacks have achieved considerable educational

gains; black enrollment in colleges rose spectacularly between

|

|

Black Student Association on Campus

|

1966, when 4.6% of college students

were black, and 1976, when 10.7% were black. Median

family income of blacks rose from $3230 in 1960 to $10142 in 1977,

but the median income of white families rose at least as fast, and

the income gap between the two groups has widened in recent years.

A major source of this differential

is the fact that

blacks tend to be barred

from

positions of authority over other workers, and are restricted instead

to lower-paying jobs further down the work-place hierarchy.

This

factor alone accounts for about a third of the total black-white

income gap. The political influence of blacks is increasing,

both in the South, where they are voting in unprecedented numbers,

and in the major cities of the North, Midwest, and West, where they

are a major voting bloc

and, in some cases, a majority.

Race

relations between black and white still leave much to be desired,

although there is unmistakable evidence of some improvements in

attitudes. However, there is a sharp divergence between the

races on the question of how much progress has been made in ending

discrimination. The majority of whites believe that there has been

a lot of progress in getting rid of discrimination, but more than

half of the blacks felt that there has not been much real change.

Only less than 20% of the whites believe that many blacks miss

out on jobs and promotion in their city because of discrimination.

Many blacks are still pessimistic about progress in race

relations. Race

relations between black and white still leave much to be desired,

although there is unmistakable evidence of some improvements in

attitudes. However, there is a sharp divergence between the

races on the question of how much progress has been made in ending

discrimination. The majority of whites believe that there has been

a lot of progress in getting rid of discrimination, but more than

half of the blacks felt that there has not been much real change.

Only less than 20% of the whites believe that many blacks miss

out on jobs and promotion in their city because of discrimination.

Many blacks are still pessimistic about progress in race

relations.

One

reason for the difference in the perceptions of the two groups may

be that blacks are more acutely aware that a great many of their

members have failed to share in the more general gains made by blacks

since the 1960s. Over the past decade many blacks, perhaps as many

as a third, have worked their way into the middle class, in the

process often moving from the ghetto to the suburbs or to better

housing within the cities. But other blacks have been left behind,

and urban

ghettos now contain a permanently impoverished

"underclass"

of habitually unemployed or underemployed black people.

Many members of this "underclass" are young and unskilled.

They live in cities where the unemployment rate for teenage black

workers runs as high as 50%, or about 8 times the rate for the American

work force as a whole. This

"underclass" could continue to persist, even in the absence

of racial discrimination, in much the same way as other pockets

of poverty persist—that is, for reasons of social-class inequality.

In any event, such progress as has been made in the past decade

has brought no benefit whatever to the black "underclass."

Living in an environment of poverty, decay, crime, drug addiction,

joblessness, and hopelessness, this ghetto underclass offers an

explosive potential for the future. One

reason for the difference in the perceptions of the two groups may

be that blacks are more acutely aware that a great many of their

members have failed to share in the more general gains made by blacks

since the 1960s. Over the past decade many blacks, perhaps as many

as a third, have worked their way into the middle class, in the

process often moving from the ghetto to the suburbs or to better

housing within the cities. But other blacks have been left behind,

and urban

ghettos now contain a permanently impoverished

"underclass"

of habitually unemployed or underemployed black people.

Many members of this "underclass" are young and unskilled.

They live in cities where the unemployment rate for teenage black

workers runs as high as 50%, or about 8 times the rate for the American

work force as a whole. This

"underclass" could continue to persist, even in the absence

of racial discrimination, in much the same way as other pockets

of poverty persist—that is, for reasons of social-class inequality.

In any event, such progress as has been made in the past decade

has brought no benefit whatever to the black "underclass."

Living in an environment of poverty, decay, crime, drug addiction,

joblessness, and hopelessness, this ghetto underclass offers an

explosive potential for the future.

Previous Page Next

Page

|